User:Wmonroe4/Vectors and Quaternions

I love vectors.

This is not a typical feeling. Most people find them either scary or completely pointless, or a combination of the two. The problem is that most people are introduced to vectors through 11th-grade pre-calculus, where their teacher shows them that there's something called a "dot product" and a "cross product", makes them do a few calculations, then moves on to limits or whatever else you do in pre-calculus. (Don't worry, I've forgotten too.)

The next place you see them, if you've gone this far in math, is Math 51, where they are mostly a notational shorthand for the solution to mind-numbing systems of linear equations, to be solved by Gaussian elimination. Gaussian elimination, if you haven't had to do it, is almost entirely arithmetic, aside from the fact that everything is stuffed into matrices. These arithmetic calculations can be done by a computer. They should be done by a computer. That is their rightful place.

This is why I was lucky to be exposed to vectors first through 3-D video game development, manipulating them by computer even before I saw them in high school. I learned about vectors by doing things with them, seeing what they mean, as opposed to what is going on with the numbers, which, frankly, does not matter in the slightest.

My hope is that working on Meru will help give you the same love for vectors that I have. The goal of this page to help you take the first step in that direction, and that first step is realizing that vectors are incredibly useful, once you no longer have to do the calculations by hand. So without further verbose introduction, I present:

How to Put Vectors and Quaternions to Good Use: A guide for game programmers

What's a vector?

It's a bunch of numbers. Or it's a thing with length and direction. These are both definitions of vector, and they're both equally valid. Since the whole point of this page is to mention the ways in which vectors are intuitive and useful, the second definition seems at first glance to be the best one to think about in day-to-day use.

There's an even more useful way to think about a vector, though: a vector is a point. This may seem strange at first. In fact, if you ask a mathematician, she'll tell you that that's just wrong, and strictly speaking, she's right—vectors and points aren't really the same. Treating them as the same thing, however, is an extremely useful practice in 3-D game programming. The most important reason is that it gives you an intuitive link between the collection of numbers and the length-and-direction "arrow" picture. Hopefully high school math has gotten you used to putting points on a Cartesian x-y plane, showing you that a point can be represented by—yes—a bunch of numbers.

But how does a point have length and direction? Well, the point isn't really the whole picture. What that bunch of numbers really tells you is the relationship between that point and some other point. That other point is the origin, some arbitrary spot that we've proclaimed to be the point represented by (0, 0, 0). The fact that we have an origin is what makes points and vectors interchangeable. Now that you have two points, just draw an arrow pointing from the origin to your point, and you've got something with length and direction. Sometimes you won't need to picture the arrow, but if you're lying awake at night wondering whether you are alone in isotropic space, it can be comforting to know that the origin is always there somewhere, throwing invisible arrows out to all your points.

What you can do with one vector

Well, you can take a look at it and examine its properties. Let's make ourselves a vector:

>>> var v = < 4, 2, -3 >; // cool new syntax!

>>> v.x

4

>>> v.y

2

>>> v.z

-3

It's clearly got a bunch of numbers. (From here on out you can assume every vector has exactly 3 numbers, unless I specifically say otherwise. A vector doesn't have to be 3-D, but we'll be working mostly with the 3-D kind, so that's what I'll be talking about.) It also has a length:

>>> v.length()

5.385164807134504

>>> v.lengthSquared()

29

lengthSquared isn't always as useful as length, but there's one major advantage to it: it's extremely fast to calculate. Finding the length proper involves taking a square root, which is a lot slower. The best use case for lengthSquared is when you are comparing two lengths: comparing the lengths-squared is faster and works just as well.

What about direction? It's kind of hard to print a direction, but you can do an okay job by coming up with a unit vector—quite simply, a vector of length 1. By arbitrarily saying that a vector must be of length 1, you're saying that you are ignoring its length and focusing only on its direction. This is how you get a normal vector in Emerson:

>>> v.normal()

{

x: 0.7427813527082074, // Emerson is printing vectors as y, z, x at the moment.

y: 0.3713906763541037, // This film edited for content and formatted to fit your screen.

z: -0.5570860145311556

}

Notice that this is in the same direction as <4, 2, -3>, our original: it's a large-ish amount in the x direction, a slightly smaller amount in the y direction, and a moderate amount in the negative z direction. You can do the math, though, or just trust the computer: this new vector has length 1. "Chopping" a vector down to length 1 like this is called normalizing the vector. Right now it's not clear why this is useful, but be patient: unit vectors come in handy in a surprising number of situations.

Normalizing a vector gives you a new vector with the same direction and a different length. There's another function that does this in a more general way, letting you multiply the vector's length by an arbitrary factor. It's called scale:

>>> v.scale(3)

{

x: 12,

y: 6,

z: -9

}

See what happened? You got a vector that was triple the length of the original, again in the same direction. There's also a function div that divides everything by the number you give it. In fact, with this, you can write normal yourself: it's just

return this.div(this.length());

This is pretty much* all the actual Emerson code does.

You can also pass in zero to scale, in which case it will just give you <0, 0, 0>, the null vector. You can even pass in a negative number, which in addition to changing its length, makes it point in the opposite direction. Of course, it's still just multiplying numbers behind the scenes. This is just what happens when you multiply all three components by zero or by a negative number. Finally, there's a special shortcut function for scaling by -1, that is, flipping the vector to the opposite direction without changing its length:

>>> v.neg()

{

y: -2,

x: -4,

z: 3

}

*There's also a minor edge case for when you try to normalize a vector of length zero, to avoid division by zero. That's all there is to it, though.

Adding and subtracting vectors

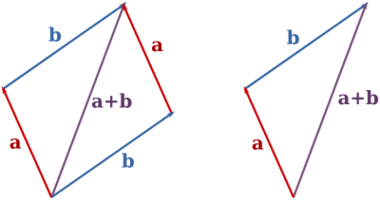

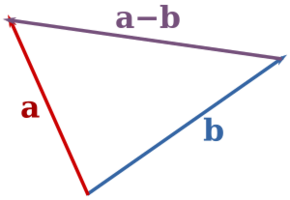

Here's where things get interesting. Pretty much all of manipulating 3-D objects is combining vectors in various ways. There are a few ways to think about vector addition. First, you can imagine sticking the tail of one arrow onto the head of the other, with the sum being a third arrow going from the remaining (non-connected) tail to the remaining head. You can also imagine this as "moving along" one vector, then from there "moving along" the other. The sum is how far, and in what direction, you moved total.

The other way to think of it is this: what point would one vector represent, if the point represented by the other were the origin? This is a particularly useful interpretation in 3-D graphics, where you can have an origin for an object (say, one of those winged frog things from Spore that we've been working with) and a vector representing a point on that object (say, the frog's left eye), which you would then add to a vector representing where the frog is in the world to get an absolute position for the left eye in terms of the whole world.

Notice how I've been careful to say "one vector" and "the other", without mentioning "a", "b", "the first", or "the second". This is because like normal addition, it doesn't matter in what order you add them. Vector addition is commutative.

From these images you might be able to guess how subtraction works. Just add the first vector to the opposite of the second. Probably the most useful way to think about this is, "how do I get from the point represented by the second to the point represented by the first?" Notice that here the order does matter—vector subtraction is not commutative. Just like normal subtraction, vector subtraction is anticommutative. That is,

<math>\vec{a} - \vec{b} = -(\vec{b} - \vec{a})</math>

or in Emerson:

a.sub(b) /* == */ b.sub(a).neg()

Why have I commented out the ==? It turns out == doesn't work for vectors, just like it doesn't work for strings in Java. Unfortunately, there isn't an equals for vectors in Emerson. You can use this function, if you really need to do this test:

function VecEquals(a, b) { return (a.x == b.x && a.y == b.y && a.z == b.z); }In any case, these are floating point numbers, so you want to be careful about comparing them.

Here's a couple of pictures to help you understand things a bit better:

Products of vectors

You probably know from pre-calculus and/or Math 51 that there are two ways you can "multiply" two vectors: the dot product and the cross product. Rather than show you all the x's, y's, and z's dancing around the page, I'll just show you another pair of pictures.

The dot product

|A| is just the length of A.

var dotProduct = vecA.dot(vecB);

So as not to give you any bad foundations, I'll say up front that the picture on the left is slightly wrong. The dot product formula, as you may remember, is not |A| cos θ but rather |A| |B| cos θ. Hence, the length in the picture is not labeled A · B: A · B is actually that length times the length of B.

The picture is correct in one important case, however, and that's when B is a unit vector. In that case, the dot product represents how much A points in the direction given by B. What if A points in the opposite direction? In that case, you'll get a negative dot product. How about if they're perpendicular? Here, they neither agree nor disagree, so the dot product is neither positive nor negative—it must be zero. The dot product of two perpendicular vectors is zero. In addition, if either vector is zero (the null vector), the dot product has to be zero: everything is perpendicular to zero.

In the general case, you can think of the dot product as measuring how much the two vectors "agree": are they going in the same direction (positive or negative?), and how far do they go (how big is the dot product?)? Double either vector, and the dot product also doubles. Double both of them, and the dot product gets multiplied by 2 · 2 = 4. It can be useful to think of projecting one vector onto the other when visualizing the dot product, but remember that neither vector is special: like normal multiplication, the dot product is commutative.

The cross product

var crossProduct = vecA.cross(vecB);

The first thing you should see in the picture on the right is that the cross product of two vectors is a vector, perpendicular to both. The area-of-the-parallelogram description isn't a bad one, as descriptions of vector math go. A cooler way to think about it is to imagine the two vectors you are multiplying ("crossing") as "legs" forming a base for the cross product to "stand on". The more stable the base, the bigger the cross product can be. For example, if you make the legs longer, the base gets bigger and therefore more stable. If the legs are splayed out in opposite directions or squished really close together, though, the base is less stable than if they are perpendicular to each other. In fact, if they're precisely in opposite directions, or precisely in the same direction, no cross product can stand on them at all—it would be free to roll and just fall over. The cross product of two parallel vectors is the null vector. This is also true if either one of the vectors is the null vector (because then you have only have one "leg"). Try it out:

>>>var right = < 0, 0, 1 >;

>>>var left = < 0, 0, -1 >;

>>>var nullVec = < 0, 0, 0 >;

>>>left.cross(right)

{ x: 0, y: 0, z: 0 }

>>>right.cross(right)

{ x: 0, y: 0, z: 0 }

>>>right.cross(nullVec)

{ x: 0, y: 0, z: 0 }

There's one last thing you need to be aware of. Here we unfortunately have to break with the vectors-are-just-like-numbers theme, because the cross product is anticommutative. This means if you flip the order of a and b in the picture above, you'll get a vector that's still of length |a × b|, but it will be pointing down, not up. This is important:

<math>\vec{a} \times \vec{b} = -(\vec{b} \times \vec{a})</math>

Just like in elementary school you got used to not being able to flip the terms on either side of a subtraction sign at will, you should train yourself not to instinctively flip the ordering of the terms on either side of a cross product sign (unless you are careful to add an extra minus sign or .neg()).

How do you figure out which direction the cross product points? You use the right-hand rule. I find it's confusing to do anything with your index and middle fingers and instead rely on the direction of all my fingers bending at once, but this is something that takes a little bit of experimentation, and works differently for everybody, so twist your right hand (make sure it's your right!) into a bunch of different shapes to see which one best helps you memorize that picture up there. You can also try one of these: http://xkcd.com/199/

What happened to my units?

If you are particularly keen on dimensional analysis, you might be a bit distressed to see that the length of the cross product is equal to the area of a parallelogram. How can an area equal a length? Aren't the two unit systems incompatible?

To resolve this conflict, I have to backpedal a little bit. The name "length" is a misnomer. Nowhere up above did I say that any of these vectors are measured in feet, or meters, or any other "unit of length". In fact, if you are that much of a stickler for dimensional analysis, you've probably taken enough physics that you're used to using vectors for velocities. A velocity isn't measured in units of length either. A more accurate term for this "length" of a vector that I've casually tossed around above is magnitude. This is a unit-agnostic term—I've adopted "length" because this is the term that Emerson uses.

We can restore your dimensional sanity thus: when you multiply two vectors, the units of the result are the units of the first times the units of the second. This is true of both the dot product and the cross product, with the added oddity that the cross product also has a direction in addition to these new, combined units. If the idea of an area having a direction seems weird to you, you can relax: directed areas don't come up too often in game programming. Velocities, momenta, forces, and torques (distance cross force), however, are very common, so don't bind yourself too tightly to the idea of a vector being a distance across space.

Quaternions

You know how I said up at the top that I love vectors? Well, I really love quaternions. All sorts of mathematical coolness comes when you wrap up a scalar and a vector in one epic structure (that's what a quaternion is, just FYI). Unfortunately, very little of that mathematical coolness is at all relevant to us, the users of the quaternion as a representation for angles in 3-D space. There are precisely three things you will need to do with a quaternion in everyday game programming experience, and none of them really require any knowledge of the internal numbers. Here they are:

Make a quaternion

There is, when you get down to it, only one way to make a quaternion that makes any sense to the average user, and that's through the axis-angle constructor. It can be shown that (weasel words for "go ask a mathematician if you want to know why this is true, because I haven't the slightest idea") any orientation in three dimensions can be reached from any other orientation by a single rotation through some angle about a single axis. If you can figure out which axis and angle you want, you can make a quaternion out of it like this:

>>>var axis = < 0, 1, 0 >; // The y axis is the vertical in Sirikata.

>>>var angle = Math.PI / 3; // Because CS is a real science, and real scientists use radians. Get used to it.

>>>new util.Quaternion(axis, angle)

{ x: 0, y: 0.5, z: 0, w: 0.8660253882408142 }

The first thing to notice is that the x, y, z, and w that make up the resulting quaternion are not just your angle and your axis. There is still some semblance of order—x and z are 0, just like in your axis. The interesting question is what happened to your angle. An astute math student should recognize the two non-zero numbers: 1/2 = sin(π/6) and (√3)/2 = cos(π/6).* In fact, the numbers that get put into the final quaternion are the result of some pretty simple trigonometry. Unfortunately, this simple bit of math is just barely enough to make most quaternions incomprehensible at first glance. This is why we generally don't put numbers into x, y, z, and w by hand, and instead rely on axes and angles. Here's some code that will grab an axis and an angle out of a quaternion, if you're curious:

function QuaternionAxis(q)

{

return < q.x, q.y, q.z >.normal(); // a unit vector in the direction of the rotation angle

}

function QuaternionAngle(q)

{

return 2 * Math.acos(q.w); // a radian angle, in the range [0, 2 * pi)

}

There is one raw quaternion you should know by heart, and it's this:

var identity = new util.Quaternion(0, 0, 0, 1);

The 1 goes in the w slot. This is called the identity quaternion. Just like the null vector represents the origin or "no distance", the identity quaternion represents the default orientation or "no rotation". (Exercise: what is the default orientation of objects in Sirikata? Set your orientation to the identity quaternion with system.presences[0].setOrientation and set your velocity along the positive x axis. Using the right-hand rule—positive x × positive y = positive z—and the fact that the positive y axis is up, figure out which direction the positive z axis points.)

*Yes, π/6. The calculations behind the scenes actually involve angle / 2, not angle. Again, if you want to know why, ask a mathematician.

Rotate a vector

If you want to do anything interesting in 3-D, you're going to be rotating vectors a lot. Here's how you do it:

>>>var rotation = new util.Quaternion(axis, angle); // same axis, angle: <0, 1, 0>, pi/3

>>>var vector = < 1, 0, 0 >;

>>>rotation.mul(vector)

{ x: 0.5, y: 0, z: -0.8660253882408142 }

This mul is a actually a flagrant abuse of a function name—multiplication of a quaternion by a vector has a well-defined meaning, and this isn't it. Inaccurate naming aside, however, having a function to rotate a vector with a quaternion is absolutely necessary for us, because the actual formula for rotating a vector involves two multiplications and an inverse (q v q-1) and would be really annoying to code up repeatedly.

Notice that z is negative here, after rotating (1, 0, 0) by a positive angle. Take some time to convince yourself that this is a counterclockwise rotation when viewed from above, following the standard convention you've used since trigonometry. (Don't forget the right-hand rule! Are the axes you're imagining correct?)

Rotate an orientation

This task doesn't come up as frequently as rotating a vector, but it can be useful at times. By "rotate an orientation", I just mean to take an object whose orientation is given by one quaternion and rotate it by a second quaternion, then check out what orientation the object ends up in. This as simple as multiplying a quaternion by another quaternion:

>>>var yRot = new util.Quaternion(axis, Math.PI / 2);

>>>var zRot = new util.Quaternion(new util.Vec3(0, 0, 1), Math.PI / 2);

>>>yRot.mul(zRot)

{ x: 0.4999999701976776, y: 0.4999999701976776, z: 0.4999999701976776, w: 0.4999999701976776 }

The one thing that you have to be careful about is the order in which you multiply things:

>>>zRot.mul(yRot)

{ x: -0.4999999701976776, y: 0.4999999701976776, z: 0.4999999701976776, w: 0.4999999701976776 }

See the negative sign on x? It turns out quaternions don't give you a break here. Quaternion multiplication is not commutative. It's not even anticommutative. You might hope that a switched sign on x is the only difference you'll ever see, but unfortunately that's only a sign of the fact that our original quaternions were 90-degree rotations about the y and z axes. Anything can happen if you switch the order of multiplication of two arbitrary quaternions (i.e. switch the order of rotation by two arbitrary angles).

How do you get your multiplication order straight?

- a.mul(b) is a quaternion that rotates first by b and then by a.

- a.mul(b) is the final orientation of an object that starts out in orientation a and is then rotated in its own reference frame by b.

These two statements are equivalent. Remembering and visualizing this is a struggle, I'm not going to lie. Try playing around with a book (one with a clearly differentiated top, bottom, front, and back), using your fingers as axes. Also occasionally put yourself in "the book's reference frame" by rotating your head so your nose is buried in the front cover and the text is right-side up to you. Hopefully you can get a feel for the way rotations combine, and figure out a way to memorize how multiplication order works.

Euler angles

One really handy use for quaternion multiplication is the ability to create quaternions from Euler/Tait-Bryan angles. This is an intuitive way to think of an orientation, in the form of three rotations put together: first face in some compass direction (yaw), then incline your head at some angle above or below the horizontal (pitch), and finally twist your viewpoint by some angle around the direction you're looking (roll). This is a common system used in applications such as flight dynamics, and it's easier to visualize than the axis-angle representation. Luckily for us, the mul function lets us compose a quaternion out of such angles fairly easily:

function EulerAngle(yaw, pitch, roll)

{

// untested code alert!

var qYaw = new util.Quaternion(< 0, 1, 0 >, yaw);

var qPitch = new util.Quaternion(< 1, 0, 0 >, pitch);

var qRoll = new util.Quaternion(< 0, 0, 1 >, roll);

return qYaw.mul(qPitch).mul(qRoll);

}

Here yaw left, pitch up, and roll CCW are positive rotations, and the opposite are negative. (Also, cool and useful fact: quaternion multiplication is associative. This means it doesn't matter whether I put qYaw.mul(qPitch).mul(qRoll) or qYaw.mul(qPitch.mul(qRoll))—it's all the same. This is not true of the vector cross product, for example, but here you can maintain a bit of your sanity.)

Orientation velocities

Like an orientation, an orientation velocity can always be represented by a rotation about a single axis. The only difference is that when constructing the quaternion, you want to pass in an angular velocity in radians per second rather than an angle in radians.

system.presences[0].setOrientationVel(new util.Quaternion(< 0, 1, 0 >, Math.PI / 6));

π/6 is 1/12 of a circle, so that code will make you spin at a rate of one turn every twelve seconds.

Objects in Sirikata rotate about their local axes, so the code above will only have you rotating in the xz-plane if you were right-side up to begin with. If you were tilted at some funny angle, you would instead rotate in whatever direction is left to you (perhaps creating a stop-drop-and-roll effect, for example). If you want to rotate an object about the absolute y-axis, you'd need to do this:

var me = system.presences[0];

var axis = me.getOrientation().inverse().mul(< 0, 1, 0 >);

me.setOrientationVel(new util.Quaternion(axis, Math.PI / 6));

Why the inverse()? What you're doing is not rotating the axis to align with the object—that's what the program does for you that you don't want! What you really want is to take an axis that's aligned with the object and rotate it back so it's in world coordinates. Hence, you need to get the inverse of the object's orientation to put the axis back into a "normal" frame of reference.