Guides/Scripting Guide/Tutorials/Send Message

Communicating with Other Entities

The primary way that a presence associated with one entity interacts with a presence associated with another entity is for the presences to send messages between each other. This tutorial will show you how to send and receive messages between presences.

In the real world, if you were going to email your friend, you would first need your friend's email address. Similarly, before Presence A can send a message to Presence B in the virtual world, Presence A must be have Presence A's "address". This tutorial will first describe how to get a presence's address, then it will explain how to send messages, and, finally, it will describe how to receive messages. It will use the example of one presence's sending another presence a request to move, and the other presence's responding to that message by moving.

Register proximity queries/discover presences

Theory

By default an entity only knows about its own presences. For an entity to discover other presences in the virtual world, it registers a query through one of its presences with the Meru system. Here's an example of such a query:

system.self.onProxAdded( userAddedCallback ); system.self.setQueryAngle(.4);

These queries take a little thinking about. Roughly translated, the first line of the above code reads: "When a presence gets near to be important to me, execute the function userAddedCallback, which the scripter has defined somewhere earlier in the program." (We will show an example of userAddedCallback that sends messages in the next section.)

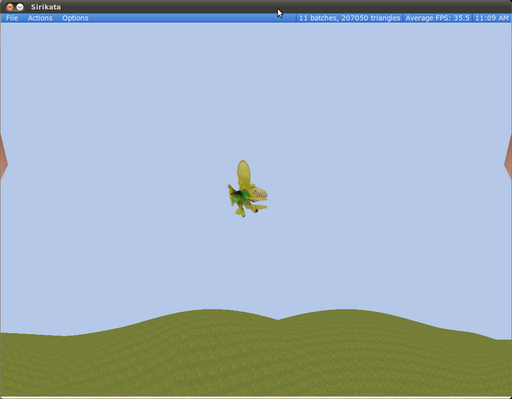

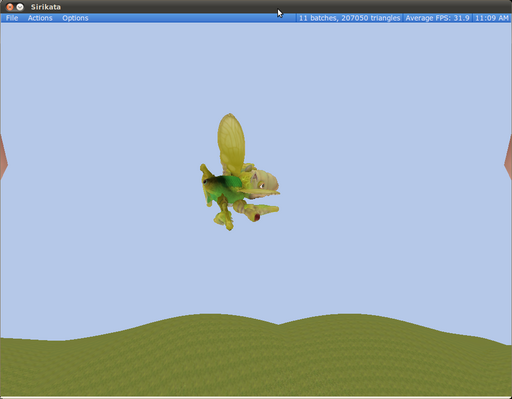

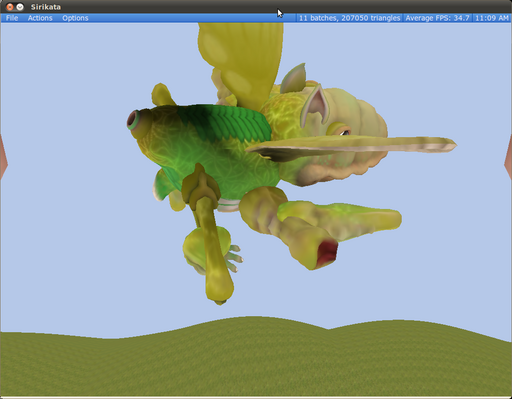

The second line of the above code actually defines what it means to be "important". Meru uses the amount of Presence A's field of view taken up by Presence B as a measure of B's importance to A. Maybe a more concrete way to think about the above is through pixels. If Presence B takes a large number of pixels on a computer monitor showing Presence A's view of the world, it is more important than if it takes only a small number of pixels to render B. In this way, presences that are nearer to A or larger are more important to A than those that are more distant and smaller. The below figures highlight relative importance. The lower figures are more "important" than the upper figures.

The bug in the above picture is less "important" than the bug in the picture below.

The bug in the above picture is less "important" than the bug in the picture below.

The bug in the above figure would be more "important" than the bugs in either of the previous two figures.

However, because of discretization and other errors caused by pixels, we don't use pixels directly. Instead we use steradians. The second line of the above code therefore reads, "A presence is important to me if it takes up at least .4 steradians of my field of view". (steradians are a measure of solid angle. You can read more about them here http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steradian. All we really want you to know is that a large steradian means that a presence would take up many pixels on your monitor; a small steradian would take up very few pixels on your monitor.)

Before moving on to the next section, it should be noted that in addition to the onProxAdded function shown above, Emerson has a complementary onProxRemoved function for presences. It looks something like this in practice:

system.self.onProxRemoved(userRemovedCallback);

Essentially, when an external presence no longer satisfies a solid angle query, the system notifies you that that presence has left the result set by calling userRemoveCallback.

Try it yourself

Enter the virtual world as an avatar. You should have just one presence associated that is connected to the space. From here, script yourself. Enter the following code into your own scripting terminal (hit ctrl + s to bring up a scripting window for yourself):

function userAddedCallback(nowImportantPresence) {

system.print("nnPresence with address " + nowImportantPresence.toString() + " is now important!nn");

}

function userRemovedCallback(nowUnimportantPresence) {

system.print("nnPresence with address " + nowUnimportantPresence.toString() + " is now unimportant!nn");

}

system.self.onProxAdded( userAddedCallback );

system.self.setQueryAngle(.4);

Now, move closer and farther from other presences in the virtual world. You should see the print message associated with userAddedCallback when you get very close to an presence, and you should see userRemovedCallback when you move away from that presence after being more distant.

You can monkey around by changing userAddedCallback and userRemovedCallback to do more elaborate things, for instance, rotating your avatar in a circle on each message.

Send message

The previous section should have explained to you how to discover presences in the virtual world. However, even if you know the address and existence of a presence how can you interact with it?

The way that presences on distinct entities interact in Emerson is through messages. This section explains how a scripter would create and send a message to another presence. To do so, let's start by re-using a little code from the previous section:

function userAddedCallback(nowImportantPresence) {

system.print("nnPresence with address " + nowImportantPresence.toString() + " is now important!nn");

...

We will be changing the contents of this function.

...

}

function userRemovedCallback(nowUnimportantPresence) {

system.print("nnPresence with address " + nowUnimportantPresence.toString() + " is now unimportant!nn");

}

system.self.onProxAdded( userAddedCallback );

system.self.setQueryAngle(.4);

As mentioned in the previous section, the Emerson runtime system will automatically execute userAddedCallback when a new presence consumes more than .4 steradians of presence[0]'s field of view. What we didn't mention before was what the runtime binds to nowImportantPresence (the argument of userAddedCallback) how it can be used. nowImportantPresence corresponds to an Emerson visible object.

To simplify sending messages, Emerson provides "angle-angle" syntax below.

function userAddedCallback(nowImportantPresence) {

system.print("nnPresence with address " + nowImportantPresence.toString() + " is now important!nn");

//create a new message

var moveMsg = new Object();

moveMsg.action = "forward";

moveMsg >> nowImportantPresence >> [];

}

The line moveMsg >> nowImportantPresence >> [], handles message-sending, where moveMsg is an Emerson object (that does not have data written into the reserved fields seqNo, streamID, and makeReply), nowImportantPresence is the intended recipient of the message, and [] will be described in section :ref:`msgResponse`. That's all there is to it. You can now send messages. The next section will describe how to react to messages that you receive.

Receive Message

In general, a scripter may want to perform different actions depending on the type of message that his/her presence receives and who that message is from.

Emerson provides custom "angle-angle" syntax to make this process easier.

For instance, examine the following code snippet:

function actionMsgCallback(msg,sender) {

system.print("I got a message with action: " + msg.action);

}

actionMsgCallback << [{'action'::}];

In English, the last line of the above code states, "If any presence connected to this entity receives a message that has a field entitled action in it, then call the function actionMsgCallback."

One can also create more elaborate patterns for matching. For instance,

actionMsgCallback << [{'action'::}] << someSender;

the above line of code transalates to "Call actionMsgCallback if any of my presences receive a message from someSender that has an action field."

actionMsgCallback << [{'action':'forward':}] << someSender;

And the above line of code transalates to "Call actionMsgCallback if any of my presences receive a message from someSender that has an action field that has the value 'forward'."

actionMsgCallback << [{'action':'forward':}, {'seqno':3:}] << someSender;

And the above line of code translates to "Call actionMsgCallback if any of my presences receive a message from someSender that has an action field that has the value 'forward' and has a field named 'seqno' with value 3."

To match any message, with any fields, scripters currently, must enter:

actionMsgCallback << [new util.Pattern()] << someSender;

This is because of a compiler bug, which will be fixed in the next released version of the code.

Message Responses

In section :ref:`secSendMsg`, you may have noticed the funny [] at the end of message send statements. This section describes how you can use this final statement in the angle-angle pipeline to to support message-response pattern of communication (A sends a message to B, B responds to that message, A responds to B's response, etc.).

The array at the end of the message sending statement can have zero to three fields. The first field is a function that describes what to do if a message sender receives a response to his/her message. For instance, if you simply want to print "I got a response", whenever you receive a response to one of your messages, you would do the following:

function printOnRespFunc(msgResp,msgRespSender)

{

system.print('\n\nI got a response\n');

}

msgToSend >> receiver >> [printOnRespFunc];

By default, the system executes the printOnRespFunc when a receiver replies to your message. The receiver's reply is placed in the argument msgResp and the receiver (as a visible object) is placed in the argument msgRespSender.

The system automatically stops waiting for a response after 5 seconds pass. Any response that you receive after this time will not trigger printOnRespFunc to execute. If you want to listen for a response for a longer or shorter time, you can provide a second argument to the sending array. For instance, if you instead want to listen for a response to your message for a full 10 seconds after your message has been sent, you would change the last statement to:

msgToSend >> receiver >> [printOnRespFunc,10];

Finally, if you want to print "No response" if you do not receive a response within 10 seconds, the send array takes a third parameter:

function printOnRespFunc(msgResp,msgRespSender) {

system.print('nnI got a responsen');

}

function printOnNoRespFunc() { system.print('nNo responsen'); }

msgToSend >> receiver >> [printOnRespFunc,10,printOnNoRespFunc];

The above code describes how one would catch a response, but does not explain how one would actually generate a response. Consider a new example where instead of printing "I got a response", you want to instead echo back any responses that you receive to your first message. This is simply done through the makeReply function that the system appends to each message:

function echoOnRespFunc(msgResp,msgRespSender) {

msgResp.makeReply(msgResp) >> [echoOnRespFunc, 10, printOnNoRespFunc];

}

function printOnNoRespFunc() { system.print('nNo responsen'); }

msgToSend >> receiver >> [printOnRespFunc,10,printOnNoRespFunc];

makeReply takes a single argument, an object that you want to send to whoever sent you a message in response to the message that that presence sent you. If for instance, you wanted to send an empty object in response to any message that you received, you would change the body of echoOnRespFunc to state: msgResp.makeReply({}) >> [echoOnRespFunc, 10, printOnNoRespFunc];.